RUSCHA EDWARD (né en 1937)

Me and The

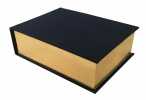

2002 Tampa, FL: Graphicstudio, U.S.F., 2002, 133x182x56mm, 576 pages non paginées, tranches dorées, relié sous couverture toilé bleu nuit.Signé et numéroté au colophon 136/230 +21 AP. (104213)

Reference : 104213

Un "Livre sculptural" signé par Ruscha, les mots "Me" et "The" imprimés sur la gouttière du bloc de texte qui apparaissent lorsque l'on courbe les feuilles d'abord dans un sens puis dans l'autre. Une feuille d'information de l'éditeur et jointe. État neuf.

Bookseller's contact details

Librairie Chloé et Denis Ozanne Déesse sarl

M. Denis Ozanne

21 rue Monge

75005 Paris

France

+33 1 48 01 02 37

Payment mode

Sale conditions

Conforme aux usages de la librairie ancienne et moderne, tous les ouvrages présentés sont complets et en bon état, sauf indication contraire. L'exécution des commandes téléphonées est garantie mais sans règle absolue, la disponibilité des livres n'étant pas toujours vérifiable lors de l'appel. Les frais de port sont à la charge du destinataire. Les livres sont payables à la commande. Nous acceptons les règlements par chèque bancaire ou postal, mandat postal ou international, carte bancaire, Visa, Eurocard, MasterCard et virements bancaires dans certaines conditions.

5 book(s) with the same title

The keepsake for MDCCCXXXIV, edited by Frederic Mansel Reynolds

London, Longman, (1833-1834). 455 g In-8, cartonnage éditeur, tranches dorées, v-[2]-312 pp., 17 gravures hors-texte.. Contient de nombreux textes littéraires dont une édition originale de Mary Shelley, ''The Mortal Immortal. A tale, by the author of Frankenstein''. La table des planches indique 16 planches notre exemplaire en compte 17 car il en contient une supplémentaire qui n'est pas citée (p. 244, The two baron par C. Heath, d'après G. Cattermole). Frottements et usures aux coiffes, rousseurs sur les planches. . (Catégories : Littérature, )

Letters to a seceder from the church of England to the communion of Rome

London, Francis et John Rivington, 1851. 490 g In-8, plein veau blond, dos orné à faux-nerfs, triple filet et encadrement sur les plats, tranches rouges, viii-326 pp.. Ex-libris Elwin Millard. Une coiffe usée, rousseurs sur les gardes. . (Catégories : Religion, )

Discourses touching the antiquity of the hebrew. Tongue and character

London, J. Knapton, 1755. 355 g In-8, pleine basane, viii-247 pp.. La pièce de titre a été refaite. Coins usés, frottements, mors fendillés. . (Catégories : Judaica, Hébreux, )

Fishbelly (The Long Dream). Traduit de l'américain par Hélène Bokanowski

Paris, Julliard, 1960. 430 g In-8 broché, 458-[1] pp., [2] ff.. Avec un portrait de l'auteur en frontispice. Première édition de la première traduction française. Cette édition contient une interview de l'auteur. Envoi autographe de l'auteur à Jean Bloch-Michel. Petites salissures et usures sur les couvertures. . (Catégories : Littérature, Littérature américaine, )

How the codex was found. A narrative of two visits to Sinai, from Mrs Lewis's Journals 1892-1893

Cambridge, Macmillan et Browes, 1893. 350 g In-8, cartonnage éditeur, [4] ff., 141 pp., [1] f., frontispice.. Edition originale du récit de la découverte d'un très important manuscrit syriaque au monastère Sainte Catherine du Mont Sinaï. Il s'agit du ''Syriac Sinaiticus'', une des plus anciennes versions de l'évangile en syriaque. Ex-libris manuscrit de Henry Fulford. Dos passé, quelques salissures. . (Catégories : Egypte, Codicologie, )

Write to the booksellers

Write to the booksellers